By some estimates, the total global cost of intimate partner violence (IPV) is $4.4 trillion, or 5.2% of global GDP, which is significantly higher than the combined costs of civil wars, terrorism, and homicides. Yet, we don’t quite understand IPV.

By Carrie Mae Weems, from the Kitchen Table Series

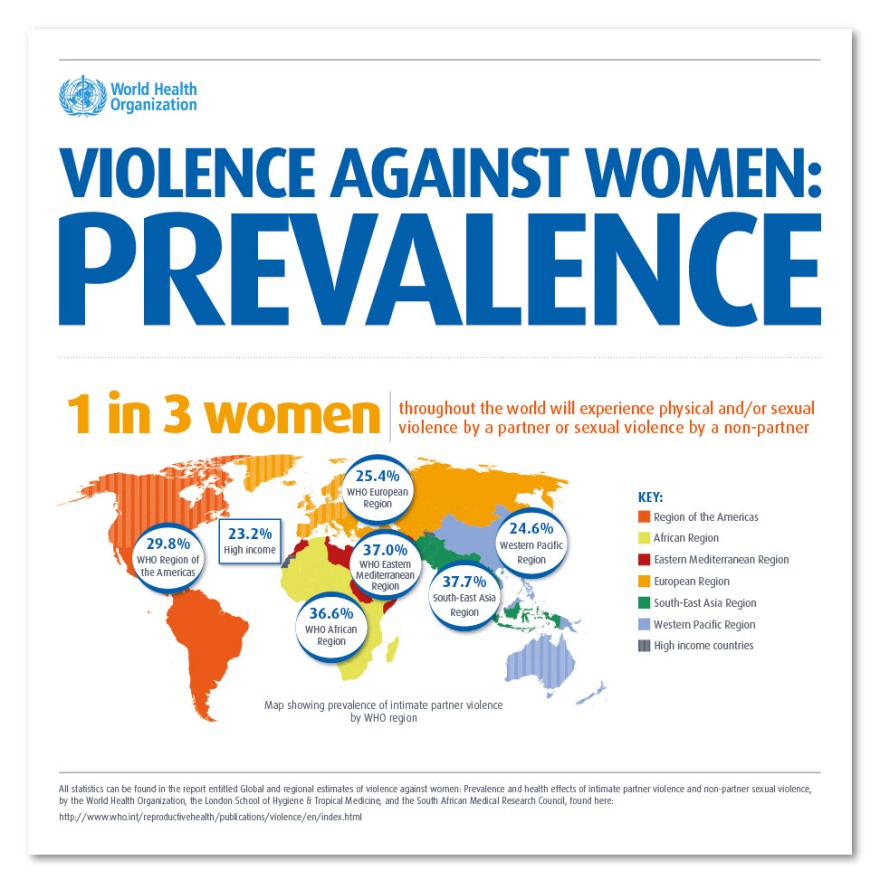

While most types of violence generally affect both women and men, the victims of IPV tend to be female; in fact, IPV is the most common form of violence experienced by women. The WHO estimates that the global lifetime prevalence of IPV among ever-partnered women is 30%, i.e., one-third of ever-partnered women have been physically or sexually abused by a current or a former partner at some point in their lives. These numbers are likely to be highly under-reported given the acceptance and normalization of IPV, the stigma associated with reporting to the police, and the fact that violent acts like marital rape are not even considered illegal in several countries.

Needless to say, it is difficult to precisely measure all dimensions of the suffering that results from IPV. However, existing data have shown that women who experience IPV are more likely to suffer from depression, to acquire sexually transmitted infections, and to abuse alcohol. Children of abused mothers are more likely to be premature or low-birth-weight, and children who witness violence between parents are not only more likely to experience violence during childhood but are also more likely to become perpetrators (if male) and victims (if female) of IPV during adulthood.

By Carrie Mae Weems, from the Kitchen Table Series

While there are several correlates of IPV—for instance, IPV is more common in poorer countries, and within countries, a higher prevalence of IPV is associated with lower incomes, lower educational attainment, and a range of factors correlated with lower socioeconomic status—causal pathways are harder to identify. Nevertheless, there has been some work in economics that has tried to identify causal factors that lead to IPV.*

Is IPV instrumental/ strategic or (intentionally or unintentionally) expressive, or both? These distinctions are relevant because they imply different approaches to reducing violence. An unexpected loss for the local football team increases the number of police reports of at-home male-on-female IPV in the US, implying that rage induced by unexpected emotional cues is relevant. A range of economic factors has also been explored, such as changes in the gender wage gap, changes in divorce laws, higher educational attainment of women, improvements in women’s labor force participation rates, and the use of violence as a signaling device to extract dowry payments. These papers paint a mixed picture.

By Carrie Mae Weems, from the Kitchen Table Series

While improved intra-household bargaining power of women seems to lower IPV in high-income countries like the US, in less developed and more gender-unequal societies, such as Turkey and Bangladesh, better work or education outcomes for women often instead lead to “male backlash,” i.e., husbands or partners inflict greater abuse in order to either counteract the higher economic status of their female partners or to use coercive instruments for extracting rents from them as women’s income rises. On the other hand, targeting cash, voucher, or food transfers towards female heads of household led to a significant decrease in the prevalence of IPV in Ecuador.

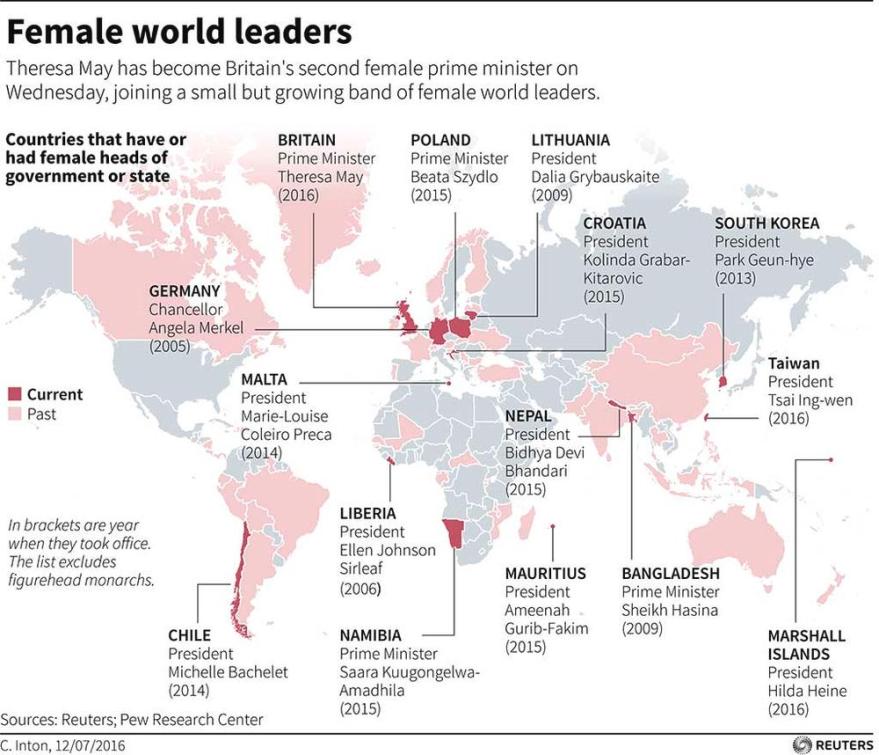

Aside from individual-level changes in women’s status, one may also wonder if a broader improvement in women’s position, say, in their political power, has any impact on IPV. In India, mandated quotas have led to a dramatic increase in the number and fraction of women in political office at the local level. Surprisingly, “there was a large increase of 26% in the documented crimes against women after the increased political representation of women.” However, this increase “is driven not by a surge in the actual crimes committed against women, but by increased reporting of such crimes due to an increase in the responsiveness of the police under women political representatives, which encourages women victims to voice their concerns as well.”

By Carrie Mae Weems, from the Kitchen Table Series

To conclude, while economists are increasingly paying more attention to spousal and domestic violence, much more work is needed. For instance, a unifying theory that can incorporate the worsening of IPV at early stages of advances in women’s position followed by an eventual decline in IPV should not be too hard. What may be harder is to design policies that can prevent the male backlash when women upset the status quo.

*This post focuses on a partial but representative literature on IPV in economics but completely ignores the large body of work in other social sciences on domestic violence. This is primarily due to space constraints but also because I am unfortunately more informed about my field. It would be great to hear from other social scientists working on these issues!

All photos courtesy: Lenny

**Portions of this post were co-authored with Petra Persson for an ongoing project.